This idea is particularly sticky because it was more or less true 50 years ago, and it's a passable mental model to use when learning sql. But it's an inadequate mental model for building new sql frontends, designing new query languages, or writing tools likes ORMs that abstract over sql.

Before we get into that, we first have to figure out what 'syntactic sugar' means.

Syntactic sugar is usually a shorthand for a common operation that could also be expressed in an alternate, more verbose, form... A construct in a language is syntactic sugar if it can be removed from the language without any effect on what the language can do: functionality and expressive power will remain the same.

That definition seems a little too loose. Is scheme syntactic sugar for x86 assembly? There is nothing that you can do in scheme that you couldn't also do in x86 assembly, and we can easily compile scheme to x86 assembly. But that doesn't seem to capture the intuition behind the phrase 'syntactic sugar'.

Let's get concrete instead. ECMAScript 2020 added some great syntactic sugar to javascript

foo ?? baris syntactic sugar for((foo === undefined) or (foo === null)) ? bar : foo.foo?.baris syntactic sugar for((foo === undefined) or (foo === null)) ? undefined : foo.bar.

What's makes these javascript examples different from compiling scheme to x86?

- The translation is local.

fooandbarcould be arbitrary expressions - we don't need to examine them or reach inside and change them in order to desugar the?.operator. - The translation is purely syntactic, as opposed to semantic. We don't need to analyze the rest of the program. We don't need to know the types of

fooandbar.

The translation from sql to relational algebra can't be local, because the sql spec has several rules that break expression subsitution. To see this in action, let's try translating some snippets of sql into relational algebra (expressed in pseudo-python because I'm too lazy to LaTeX).

We'll start with some easy rules:

translate('select a from X')

=>

translate('X').project('a')

translate('X order by b')

=>

translate('X').orderBy('b')`

This is going great. I don't foresee any problems.

Let's try something a little more complicated:

translate('select a from test order by b')

=>

table('test').project('a').orderBy('b')

That's an error, because we can't order by a column that we just projected away. Right?

postgres> select * from test;

a | b

---+---

0 | 1

1 | 0

postgres> select a from test order by b;

a

---

1

0

Ok, I guess we just did the translation in the wrong order. We should do orderBy before project.

translate('select a from test order by b')

=>

table('test').orderBy('b').project('a')

Bug fixed! Let's move on to a slightly harder case:

translate('select a+1 as c from test order by c')

=>

table('test').orderBy('c').project('a').addColumn('a+1', as='c')

That must be an error, because we can't order by a column before creating it!

postgres> select a+1 as c from test order by c;

c

---

0

1

Oh man, maybe we should look at some docs or something.

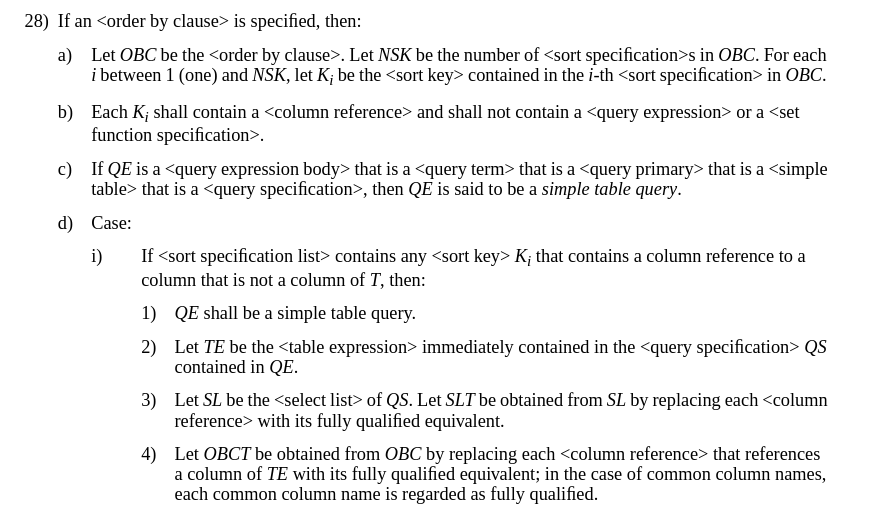

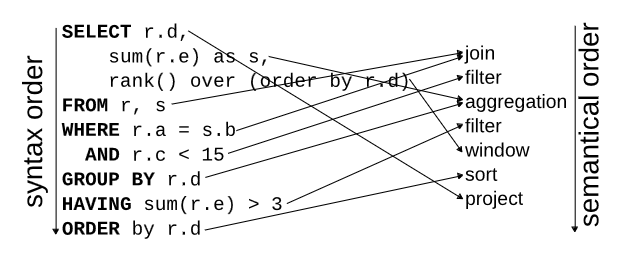

For those of you that don't speak spec, this is explaining that order by operates either on select or from, depending on what columns it needs.

What if it needs columns from both?

postgres> select a+1 as c from test order by b,c;

c

---

2

1

That's right:

translate('select a+1 as c from test order by b,c')

=>

table('test').project('a','b').addColumn('a+1', as='c').orderBy('b','c').project('c')

The order by happens in the middle of the select! But only in this specific syntactic configuration - any additional syntactic layers prevents that rule from applying:

postgres> select * from (select a+1 as c from test) test2 order by b,c;

ERROR: column "b" does not exist

postgres> ((select a+1 as c from test) union (select a+1 as c from test)) order by b,c;

ERROR: column "b" does not exist

Lest you think is just one weird corner of the sql spec, I found this helpful diagram explaining how the scoping rules work (from Neumann and Leis, 2023).

Hiding in the above is a hint that the translation can't be purely syntactic either.

In select foo.* from bar order by b, whether the order by comes before the select depends on whether the table foo has a column b. So we have to look at the database schema to know the correct translation.

A similar problem occurs in select (select a from foo where a = b) from bar. If a and b occur in foo then we can translate this as:

translate('select (select a from foo where a = b) from bar')

=>

table('foo').filter('a = b').errorIfMoreThanOneRow().product('bar').project('a')

But if a occurs in foo and b occurs in bar then... well, try to translate it yourself. Remember that it's an error for the subquery to return more than one row.

It's not just tables that produce this problem either. Functions are more complicated that they first appear:

translate('select F(a) from test')

=>

table('test').addColumn('F(a)', as='F').project('F')

That seems reasonable. What if F is sum? Then the translation should be:

translate('select sum(a) from test')

=>

table('test').groupBy().aggregate('sum(a)', as='sum')

Or what if F is generate_series?

translate('select generate_series(0, a) from test')

=>

table('test').addColumn('generate_series(0, a)', as='generate_series').unnest('generate_series')

We can just keep making this more complicated. For example:

translate('select sum(b), generate_series(0,a), sum(b*b) from test group by a')

=>

table('test').groupBy().aggregate('sum(b)', 'sum(b*b)').addColumn('generate_series(0, a)', as='generate_series').unnest('generate_series')

Both of the sums have to come before the generate_series, otherwise the unnesting will change the number of rows that we're feeding to the aggregates.

Functions can be user-defined, or installed by extensions, so we have to look at the (global, mutable) catalogue to find out whether a function is scalar, aggregate or set-returning before we can figure out how to translate the query to relational algebra.

Ok, so the translation from sql to relational algebra depends on scoping rules, which depend on type inference, which depends on the installed schema and other global state like which user-defined functions exist or which extensions have been installed.

In materialize, converting the sql parse tree to the high level IR takes ~30kloc. That doesn't include parsing, planning or optimization - the high level IR is just fully-typed, explicitly-scoped sql. Those 30kloc are just for name resolution, type inference, schema/catalogue lookups and all the other weird little non-syntactic things that have to be done to even figure out what a sql query means.

For comparison, ~30kloc is about the size of the entire lua implementation. Translating scheme to x86 assembly in the ribbit scheme only takes 3kloc! So we're definitely stretching the scope of the term 'syntactic sugar' when it comes to sql.

But will I at least concede that sql can, with much coding, head-scratching and spec-reading, be translated to relational algebra?

Well, what is relational algebra?

As I pointed out in a previous post, there isn't one definitive version of the relational algebra. The relational algebra proposed in Codd's original paper didn't even allow aggregates or ordering, so it clearly isn't expressive enough for sql. We need to add at least:

- Multisets instead of sets.

- Nulls and three-valued logic.

- Sorting and limits.

- Aggregation, grouping, windowing, partitioning.

- Relation variables (CTEs).

- Fixpoints/iteration (recursive CTEs).

- A scalar expression language with scalar and aggregate functions, collections (arrays are in the sql spec) and errors (eg

select 1/0).

I will, begrudgingly, accept that as a relational algebra. We had to add a lot more scalar and relational operators, but we preserved the fundamental properties of the original relational algebra that make it a good execution target:

- The lack of scoping rules and free variables makes it easy to rearrange tree nodes during plan optimization.

- The restriction to first-order relations makes efficient representation easy.

- The clear separation between scalar and relation expressions make the algebra very friendly to vectorized interpreters.

However, the physical plans in most sql databases do not completely preserve those properties. Almost every sql database has at least one operator that mixes the scalar and relational worlds. For example, in postgres we have the SubPlan operator:

postgres> explain select (select a from foo where a = b) from bar;

QUERY PLAN

-------------------------------------------------------------

Seq Scan on bar (cost=0.00..106816.75 rows=2550 width=4)

SubPlan 1

-> Seq Scan on foo (cost=0.00..41.88 rows=13 width=4)

Filter: (a = bar.b)

In mariadb/mysql it's DEPENDENT SUBQUERY:

MariaDB [test]> explain select (select a from foo where a = b) from bar;

+------+--------------------+-------+------+---------------+------+---------+------+------+-------------+

| id | select_type | table | type | possible_keys | key | key_len | ref | rows | Extra |

+------+--------------------+-------+------+---------------+------+---------+------+------+-------------+

| 1 | PRIMARY | bar | ALL | NULL | NULL | NULL | NULL | 1 | |

| 2 | DEPENDENT SUBQUERY | foo | ALL | NULL | NULL | NULL | NULL | 1 | Using where |

+------+--------------------+-------+------+---------------+------+---------+------+------+-------------+

Sqlite is a little weird and has actual loops in the physical plan, but in the logical plan we can see the SCALAR SUBQUERY that creates those loops:

sqlite> explain query plan select (select a from foo where a = b) from bar;

QUERY PLAN

|--SCAN bar

`--CORRELATED SCALAR SUBQUERY 1

`--SCAN foo

In cockroachdb it's apply-join:

movr> explain select (select a from foo where a = b) from bar;

tree | field | description

------------------+-------------+--------------

| distributed | false

| vectorized | false

render | |

└── apply-join | |

│ | type | left outer

└── scan | |

| table | bar@primary

| spans | FULL SCAN

You get the idea.

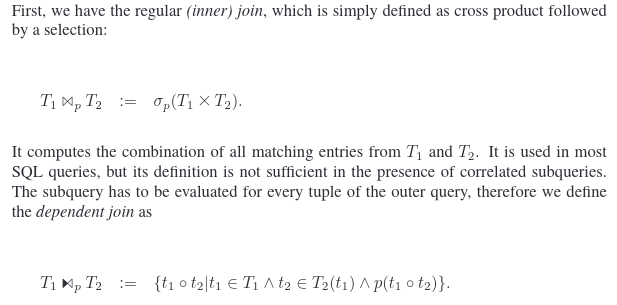

The first argument to the SubPlan operator is a regular relational expression. The second argument is a relational expression with free scalar variables - alternatively you can think of the second argument as a function from rows to relations. The operator loops over each row in the first argument, and for each row evaluates the second argument and takes the product of the row and the resulting relation. Then all those resulting relations are unioned together.

The SubPlan operator is used to execute scalar subqueries, IN/EXISTS, lateral joins etc because the semantics of these sql operations are very difficult to translate to relational algebra.

It's hard to figure out exactly when sql gained this expressivity. According to wikipedia the first commercial sql database was released in 1979. The sql-86 spec specifically requires that subqueries do not contain free scalar variables. By sql-92 this language was gone. That gives us a window of at least 13 years during which relational algebra might have been a reasonable mental model for the semantics of sql.

For the next 23 years pretty much all databases would have needed something like the SubPlan operator.

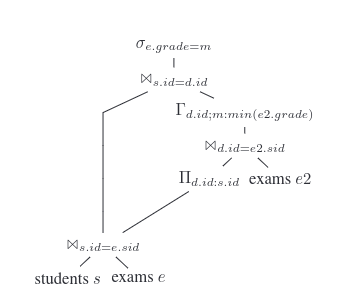

In 2015, Neumann and Kemper published an Unnesting Arbitrary Queries which explains how to translate any sql query to a kind of relational algebra. To even explain the problem they had to add new notation to the relational algebra:

Unfortunately the resulting plans are dags rather than trees, which makes downstream optimization harder:

To my knowledge, only tableau, materialize and duckdb actually use this method. Other sql databases all have some queries for which they resort to something like SubPlan.

To summarize: for most of the history of sql we did not know how to translate it to relational algebra, and now that we do know most databases still don't do it.

This may all sound pointlessly picky, but good mental models are important:

- If you're learning sql, learn the scoping rules up front. It will save confusion later.

- If you're designing an orm or query builder, you should think about how to calculate the scoping rules and how to express subqueries / lateral joins (eg).

- Sql started with non-nested relations and ended up having to add a mishmash of different and inconsistent constructs that combine creating and flattening nested relations. If you're designing a new query language, support nested relations and scalar->relation functions from the beginning. (It's not too hard to design typing rules that guarantee that nested relations can always be optimized away.)

- If you're trying to build a formal model for sql (eg for fuzzing your database or proving optimizations correct) then don't start from first-order relational algebra - you won't be able to handle the whole language. Something like the nested relational calculus might be a better starting point, and depending on the application it might be easier to ignore scoping/typing rules and starting from something like materialize's high level IR.

Find more unexplanations here.